Building a Futures Market Making Bot - Winning the UChicago Trading Competition, Part 1

Back in April, I participated in the UChicago Midwest Trading Competition with a couple of friends, and we ended up winning 2 out of 3 cases and the overall competition. So I’ve procrastinated on writing this blog post for 3 months, but I needed to get this out before I start working at a trading firm in a few weeks. This is the first part in (hopefully) a series of my favorite trading cases.

First, let me take you through how we tackled one of my favorite cases, building a futures market making bot on the Chicago Electricity Futures Market.

The Case

You are a market maker on the Chicago Electricity Futures Market. Real electricity trades daily between consumers and producers on the Chicago Electricity Spot Market, but the futures market is where traders bet on the price of electricity in the future. For instance, an electricity producer could sell 10 MWh of December futures to lock in the price of their electricity in December, thus hedging against the price of electricity. There are 4 futures contracts which expire on the last day of June, August, October and December. These future contracts are cash-settled, so they settle to the current spot price of electricity upon expiry.

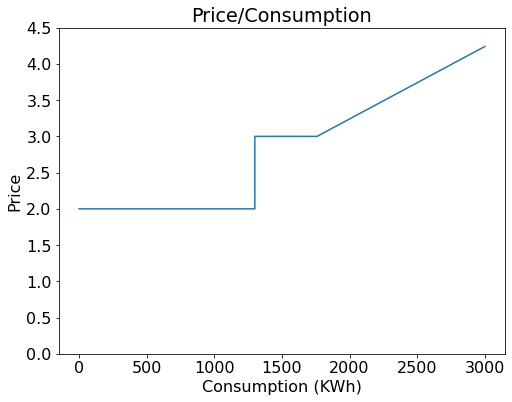

Here’s how the electricity spot market works. Chicago produces electricity in 3 ways: Natural Gas generators ($2/MWh), coal generators ($3/MWh), and peaker plants. Electricity is consumed in that order, first natural gas, then coal and finally the peaker plants. Each year, the city starts out with fresh capacity of natural gas (around 1300MWh) and coal (around 450MWh), and moves onto the next source once the previous is exhausted. Peaker plants are special - they start at $3.001/MWh and do not run out, but each extra MWh produced costs $.001 more than the previous. This is what the price/consumption graph looks like.

Each day, consumers purchase a random amount of electricity. Each day, you also know how much they used the previous day before you start trading. Note that you cannot buy or sell electricity on the spot market itself, you can only observe it.

As a market maker (MM), your job is to facilitate trading of futures contracts by reducing the spread in the market, which lower costs of transactions for traders. Take a market with bids for $1.50 and offers at $2.00. A ‘fair’ price of the contract would be $1.75, the mid price. However, the $.50 spread between the bid and offer makes it impossible to trade at the fair price. You (a MM) could come in and bid for $1.60 and offer at $1.90, decreasing the spread from $.50 to $.30. Someone who buys a stock pays $1.90 for it instead of $2.00, saving $.10, while you make the difference between $1.90 and the ‘fair’ mid price of $1.75. If someone else then sells a contract to you at $1.60, you have made a clean profit of $.30 without a resulting position in the contract, and everyone’s happy. But it’s not that simple: If the contract price rises to $2.00 after your sale, then you have made a loss of $.10. Also, another market maker could come into the market to bid for $1.70 and offer at $1.80, taking away your profits.

To make money market making, you have to be smart - know the value of the contract by predicting the price of electricity in the future. You also need to be aggressive - provide your best price to the market to make more profitable trades. Therefore, a successful bot requires 3 components: a good guess for the ‘fair’ price of the contract, a bot which trades aggressively but minimizes risk taking, and a way to augment the dumb bot with human intuition. I will discuss each of these parts below.

What’s our fair?

We first try to compute our ‘fair’, a prediction of the price of the 4 future contracts. Let’s do this in a Jupyter Notebook!

Execution matters

During the competition, all teams have a position limit of 1000 lots in each contract. This means that you are not allowed to be long or short more than 1000 lots of each contract. In the real world, market makers are similarly limited by the amount of risk they can take with their capital. Teams are effectively limited in the amount of trades they can make, so no one can dominate all of the trades in the market.

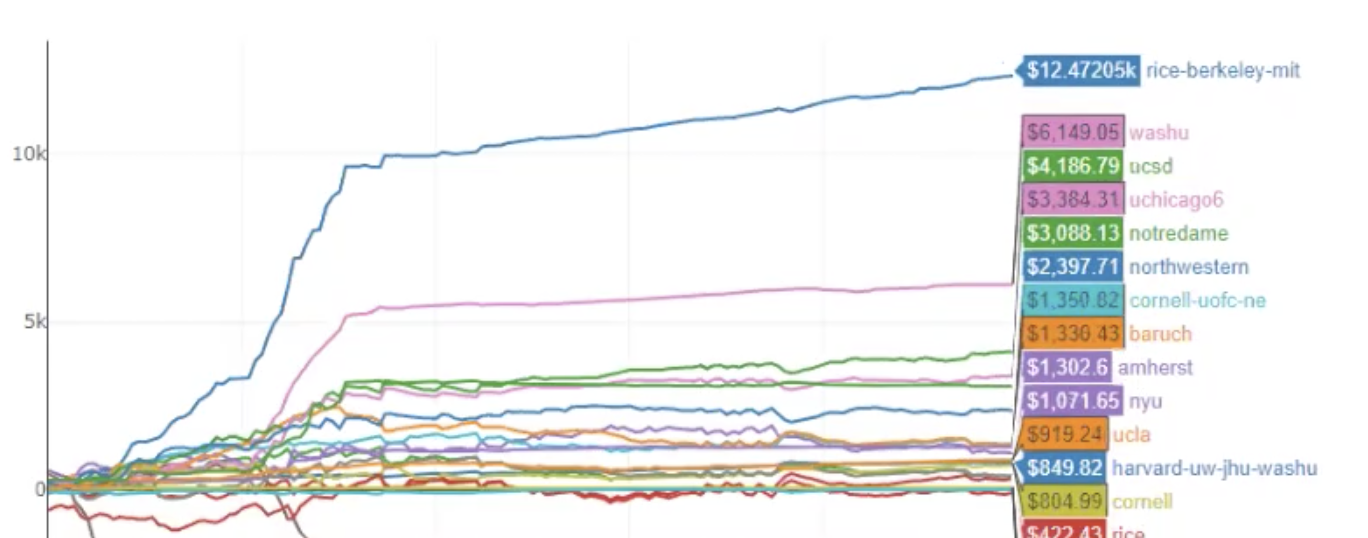

This is the profit and loss (pnl) chart of one of the rounds. How did we (rice-berkeley-mit) manage to make more profit than the next 2 teams combined? Ultimately, I think most of our edge came from how we traded more aggressively and managed our position limits more intelligently, such that our trading volume was multiples of what other teams did.

This is the profit and loss (pnl) chart of one of the rounds. How did we (rice-berkeley-mit) manage to make more profit than the next 2 teams combined? Ultimately, I think most of our edge came from how we traded more aggressively and managed our position limits more intelligently, such that our trading volume was multiples of what other teams did.

In this section, I want to break down our market making strategy by building up pieces of our strategy from a naive market making bot. We’ll discuss various test cases of market situations which a naive bot fails on, and strategies our bot used to profit from.

The naive market making bot

A naive MM bot takes in a fair as input, and asks for an edge around this fair. A size variable For instance, fair = $3.50, edge = $.10, size = 100. At each time interval, the bot places a bid into the market for 100 lots for $3.40, and places an ask for 100 lots at $3.60. Essentially, the MM is asking for an edge, or expected profit, of $.10 for each trade that it makes.

Case 1: The informed customer

A trader enters the market with information that the fair price is $3.70. (We still think fair = $3.50.) For ten successive days, the traderbuys 100 lots from us at $3.60. After the contract expires at $3.70, we have made a loss of $.10 * 1000 = $100. Could we have done better? Should we have sold the last 100 lots to the trader at $3.60, despite being short 900 lots already?

We could be more averse to taking on large, unbalanced positions, and this can be represented by the fade parameter. Let fade = $.02. That means for every 100 lots of position we take, we will augment our fair price by $.02. After selling 500 lots (thus short 500), our new fair is $3.50 + $.10 = $3.60. Our new market is $3.50 at $3.70. The trader will stop buying from us because he will not make a profit anymore. With fading, we ended up selling 500 stocks at an average price of $3.65, making a loss of $25, a big improvement.

Case 2: Competing with other market makers

It’s nice to be able to make a $.10 edge on each trade, but with 15 other market makers in the market, you won’t get to make any trades. So let’s reduce our edge to $.05. What happens in situations where there are no other market makers quoting in the market? Should you be satisfied with only $.05 in edge?

This is where we have to start considering the action of other market participants. We look at the book, a collection of all bids and asks on the market (and their respective sizes) to know what other traders are doing. We introduce the slack parameter, which represents flexibility in our edge. Say slack = $.10. Then, we vary our edge from $.05 to $.15 depending on market conditions. If there are no other MMs on the market, we would present our bids and asks with an edge of $.15, so $3.35 at $3.65 in the above example. If there is a competing bid of $3.40, then we will ‘penny’ that bid by changing our bid to $3.41. By improving our price by a penny, we ensured that any customer trade will be executed with us first. This pennying mechanism ensures that we make the most trades possible, while making the most from each trade. This is one of the biggest differentiators you can implement in trading competitions, as it lets you trade significantly more trades. There are some intricacies you have to pay attention to, such as making sure that we remove our own orders from what’s reported in the market feed. This is crucial in preventing our bot from bidding against itself.

Case 3: Building scales

An uninformed customer comes into the market and buys up all of the offers on the market, and still wants to buy more. Because you don’t have more orders on the market, you missed out on selling to the customer at a great price. We can avoid this problem by building scales - multiple levels of bids and offers at increasing edges. For instance, we can offer 100 lots at $3.60, $3.80, $4.00, $4.20 etc. Most of the time, these extra orders will not be traded against, but due to the immaturity of our competition market, we get to trade at $3.80 or $4.00 with reasonable frequency and end up making a massive EV from the trade.

That’s basically how our bot traded. These strategies have insane benefit for their implementation complexity, but most other competitors stopped at case 1 or case 2. Tuning the parameters for edge, fade, size and slack is also crucial in maximizing pnl. While we can tune these on the provided test exchange, these may not work on the real competition due to more competition, so we need the flexibility to tune parameters during live trading.

Day of the competition

We built a monitoring interface to tune parameters during live trading. The column titles are futures ticker | our bid size | our bid price | fair | our ask price | our ask size | position change in last tick | current position.

During live trading, we mainly focused on our position change and current position. If our trading volume decreases, then we can decrease our edge appropriately to to gain more volume. If our position becomes too imbalanced and does not revert quickly, we can increase our fade to revert our position quickly.

To dynamically change our trading parameters (and any other part of the bot), we used exec to read an execute an arbitrary params.py file. Here’s what params.py looks like.

self.max_pos = 950

self.params = {}

self.params['EFM'] = {

"edge": .005, # One sided edge from fair

"fade": .005, # Fade per 100 delta

"size": 100, # Size of trade

"edge_slack": .10 # edge to ask for beyond min edge

}

otherparam = {

"edge": .002,

"fade": .001,

"size": 100,

"edge_slack": .10

}

for c in ['EFQ', 'EFV', 'EFZ']:

self.params[c] = otherparam

Conclusion

Trading is a secretive industry and there are little tutorials out online for how to get started. I only got my start after a lucky internship offer from a trading firm. So if you’re a college student who read this blog post and think you’re interested in trading, consider participating in Traders@MIT, Midwest Trading Competition and the Rotman International Trading Competition. I hope this blog post inspired you to try building a trading bot and gave you a head start!